The 1940s brought Wright new challenges. Wright encountered success and failure throughout the 1940s. His strong anti-war stance, especially after the attack on Pearl Harbor, brought government blackballing to his extensive wartime housing projects, including the Cloverleaf housing scheme. His Utopian ideals couldn’t be destroyed, even in the course of a global conflict. Wright’s own apprentices attempted to live up to these ideals, refused to serve and ended up in prison.

Wright was a man who placed enormous respect on individuals or groups that took risks or bucked the status quo. He visited the Soviet Union in the 1930s without reservation, excited by the grand social experiments underway (without knowing or understanding how the Stalinist state would evolve). Without any government contracts Wright focused on his residential projects, as well as his design for a certain New York museum.

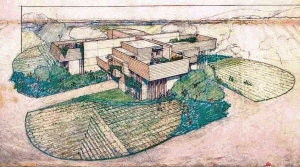

Most of his best Usonian housed were created during this period, including many of his “Automatic” designs; they were a modernization of his early textile block plans from the 1920s.

It was also during this period that Wright designed two of his most forward looking projects (though unbuilt): the Point Park Civic Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and the Rogers Lacy Hotel in Dallas, Texas. The Point Place project was a massive mega-structure of concrete and twin towering cable stayed bridges spanning Pittsburgh’s rivers. The Rogers Lacy would have been a sleek glass walled skyscraper (very similar in appearance to Daniel Libeskind’s early Freedom Tower concept from 2002).

Wright’s creativity and output during the 1950s was incredible. Several of his most famous and radical structures, came from this fertile period. The Beth Sholom Synagogue in Pennsylvania is a building straight out of a science fiction movie, with its towering peak, illuminated from within; standing as a beacon of faith for the Jewish community. The Price Tower in Oklahoma, Wright’s only high-rise, was built during this time as well. Again, several of his most imaginative projects stood only on paper: A mile tall building for Chicago, a massive museum for Ellis Island, and a beautiful state capitol for Arizona; like he was fond of saying: “I shake them out of my sleeve.”

The masterwork of this period was designed for Solomon R. Guggenheim, a very wealthy American business man and lover of modern or “non-objective” artworks. In the 1920s Wright had worked on a concept planetarium called the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective for Sugarloaf Mountain in Maryland. Wrights’ concept involved a large inverted ziggurat structure for tourists. It was meant to accent the brow of the hill with its conch shell like form and gleaming white surface.

The Guggenheim Museum grew from the early ziggurat concept into the inverted bowl that makes up the existing structure. During the prolonged design phase, Wright encountered ferocious opposition to his various design choices, many of which were unorthodox structural solutions that had never been in museums before (indirect lighting, sloping display walls, and the curving angled ramp). Many architectural critics, not to mention the artists, were unconvinced that the Guggenheim would be an ideal display space for actual “ART.”

I am of the opinion that the museum is in itself a fabulous work of sculpture, springing out of the tight lot upon which it sits, displaying its sensuous curves to passerby…and when they actually enter the fast central atrium, with its skylight pouring down brightness and life; they are transported to an ethereal realm, where the objects hosted within pale in comparison to the host. Wright obviously understood the irony of his designing such a structure to honor the very kind of art he despised, but nevertheless created a most astonishing building for it.

Just six months before the grand opening Wright passed away. The man was 92 years old. His creative career had spanned the 19th and 20th centuries. Throughout the loves and losses of his life he strove unceasingly to be true “to thine own self.” Far be it for a man to be held above others, yet he towered dynamically over his closest artistic rivals, where his iconoclastic nature engendered a level of respect in them for him.

Though his flesh had failed, though his fingers were lifeless—his ideas lived on, inspiring future generations far removed from his own.

He was the architect of his own spirit and that was his greatest masterpiece.

more about “Automatic Houses”: http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/PhRtUsonAuto.htm

Leave a comment